By Paul Reynolds

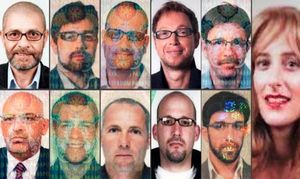

By Paul ReynoldsThe British government is expected to announce the expulsion of an Israeli diplomat in connection with Israel’s alleged misuse of British passports – a number of which were carried by a hit squad that assassinated Palestinian Hamas official Mahmoud al-Mabhouh in Dubai.

In February, the government set up an investigation into the matter.

At the time, official language in announcing that the Israeli ambassador in London Ron Prosor would be going to the Foreign Office was notably moderate.

A statement said simply that “given the links to Israel of a number the British Nationals affected, there will be a meeting between the FCO Permanent Under Secretary and the Israeli Ambassador tomorrow”. This was an invitation not a summons.

It was, in February, a matter of Britain asking questions, not making protests and taking retaliatory action (such as demanding an apology, restricting official contacts or even expelling the ambassador for a time).

During his meeting with Mr Prosor, the permanent under-secretary Sir Peter Ricketts asked for full Israeli co-operation with the British inquiry. This may have proved problematic if Mossad was involved. Israel would not want to reveal too much. So a lot depends on how the word “cooperation” is defined. A total failure to cooperate would trigger a British response.

Promise

One complicating factor is that in 1987, the Israelis promised Britain that it would not use British passports in secret operations again.

On that occasion, eight British passports reckoned to be for Mossad agents were found in a bag in a West German telephone booth.

The then Israeli ambassador in London, Yehuda Avner, did find himself on the receiving end of a British protest.

If it turns out that the assurance given then has been broken, the British diplomatic reaction will be more severe.

Britain might also press other European countries whose passports have surfaced in this affair – Ireland, France and Germany – to take a firm line.Ritual element

However, these events have a certain ritual about them. New Zealand got angry with Israel in 2004 when two Israeli agents were found to be using New Zealand passports. Diplomatic ties were frozen, but were quietly resumed a year or so later after an Israeli apology.

In 1987, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher did order the closure of the Mossad station in London for a time – though no doubt it carried on in different ways – after the kidnapping of the Israeli nuclear whistleblower Mordechai Vanunu.

But that did not affect her support for Israel and in due course, normal service resumed.

If it finds the evidence this time, Britain will no doubt demand satisfaction. But neither Britain or Israel will want this to escalate into a full-scale row.

The British Prime Minister Gordon Brown is sympathetic to Israel and there is a delicate intelligence relationship that needs to be preserved as far as possible in view of the threat to both countries from Islamist extremists.

Difficult relationship

This might well be one of those bumps in the road that have dogged British-Israeli relations for decades, going back even beyond the founding of the State of Israel in 1948.

It has rarely been an easy relationship and has been marked by contradictions, resentment and touchiness on both sides.

The historic promise from Foreign Secretary Lord Balfour in 1917 that Britain would establish a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, while also promising that the “civil and religious rights” of the “existing non-Jewish communities” would not be prejudiced, proved impossible for Britain to deliver.

Britain found itself having to put down a Palestinian-Arab revolt in 1936 only to be attacked by Jewish groups wanting Britain out of Palestine after World War II (though during the war there was strong Jewish support through the formation of the Jewish Brigade of the British army). Britain pulled out of Palestine in anger and chaos.

The Israelis complain that Britain reneged on the Balfour promise in a White Paper in 1939 which rejected the concept of a two-state solution and severely restricted Jewish immigration at a time when Jews were being murdered by the Nazis.

Reliance on US

For years, there was a strand in the British Foreign Office that was hostile to Israel.

Britain delayed recognising Israel as a state for eight months. The US did so within minutes. You can occasionally hear echoes of that hostility in London, but there are really only echoes, not policy.

Things improved in the 1950s and 60s. In fact, Britain and France were Israel’s main weapons providers then, not the United States. Israel won the 1967 war with French aircraft and British tanks. And in the Suez operation in 1956, Britain and France colluded with Israel in the invasion of Egypt, until the US pulled the plug.

Then, Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath slapped an arms embargo on Israel and other combatants in the 1973 war, and Israel has relied on the US ever since.

It no longer puts its trust in any European government, though it likes their goodwill.

The Europeans try to balance their support for Israel as a state with their sympathy for the Palestinians as a people. They also have to be mindful of their relationship with the Arab world as a whole.

Relations at the best of times can turn touchy. There is currently a row over the British system of allowing magistrates to issue arrest warrants for alleged war crimes and, according to Israel, the British government has been too slow in changing this.

Incidents like Dubai make maintaining a balance more difficult.

http://intifada-palestine.com/2010/03/another-bump-in-the-road-for-british-israeli-relations/

No comments:

Post a Comment